Brent Pollard

The Unexpected Birth of a Christmas Tradition

Christmas Day 2025 has already passed. In Japan, where Shinto and Buddhism are part of daily life, Jesus Christ is often seen as just one deity among many—if acknowledged at all. As a result, most Japanese do not observe Christmas as a religious holiday on December 25. Instead, the holiday has become a romantic occasion for couples, more like Valentine’s Day than a Nativity celebration. Interestingly, since the 1970s, a tradition has persisted: to properly celebrate Christmas in Japan, people should eat fried chicken, especially from KFC.

This story shows how easily tradition can take hold in fertile ground. Takeshi Okawara, Japan’s first KFC manager, allegedly heard foreigners complain that turkey was hard to find in Japan, so they had to settle for chicken during Christmas. This casual remark inspired an idea. Okawara saw a chance to promote “party barrels” as the perfect Christmas celebration. Since Japan didn’t have strong Christmas customs, KFC found a valuable niche in the food industry, which was exactly what the franchise needed to grow.

How Marketing Became Tradition

In 1974, KFC Japan introduced its famous Kurisumasu ni wa Kentakkii! campaign—”Kentucky for Christmas!” The campaign’s success surpassed expectations. By 2019, around 5% of KFC Japan’s yearly revenue came from Christmas sales. During the holidays, customers must pre-order their party barrels weeks ahead since they sell out fast. Long lines form outside locations featuring Colonel Sanders statues dressed as Santa Claus, blending commercial symbols in a way that might surprise Western observers.

If you asked the Japanese about their Christmas tradition, they’d surely say fried chicken is the holiday’s proper food. Many are surprised to learn Americans eat turkey, not KFC, on Christmas. Interestingly, young Japanese now prefer KFC for Christmas because their grandparents started this practice long ago. In only 51 years, what started as a marketing stunt has become a genuine part of Japanese culture.

The Innocence of Cultural Misunderstanding

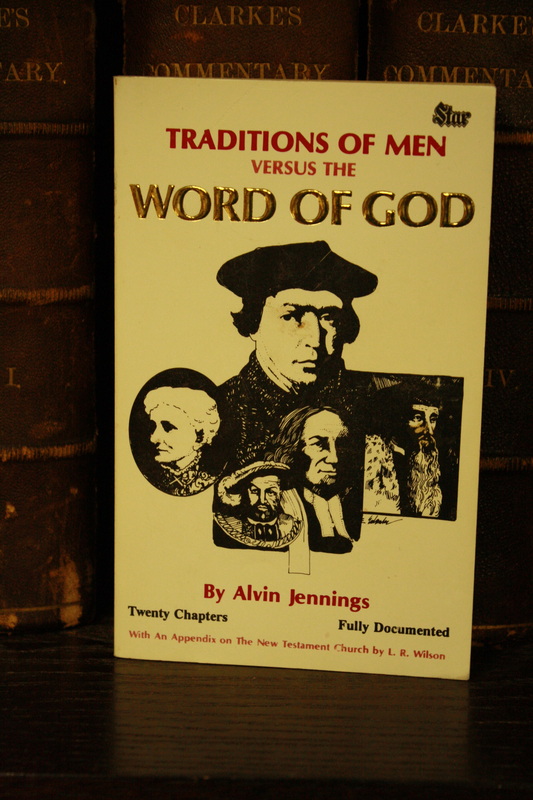

Japan’s misinterpretation of Christmas customs is harmless—simply a mistaken understanding of cultural practices far removed from their roots. However, this highlights a deeper spiritual risk that requires our careful reflection. We tend to be creatures of habit, often confusing familiarity with genuine faithfulness. What starts as an innovation by one generation can quickly become a duty for the next, leading us to forget to question whether our actions are truly aligned with the truth.

When Jesus Confronted Tradition

However, some customs require our careful attention. Jesus Christ sharply criticized the religious leaders of His era because they forsook God’s commandments to prioritize their traditions (Matthew 15:3; Mark 7:8-9, 13). His words resonate through time: “You are experts at setting aside the commandment of God in order to keep your tradition.” (Mark 7.9 NASB95)

If you had asked these leaders about their practices, they probably would have confidently claimed that their traditions fully aligned with Moses’ Law. These customs, after all, had been preserved through generations of faithful Jews, supported by the weight of history and validated by respected teachers. Certainly, this alone demonstrated their legitimacy.

The Sovereignty of God’s Word Over Human Custom

Yet Jesus, with divine authority, revealed how these traditions deviated from His Father’s original commands. This offers a serious warning to all generations of believers. God’s sovereignty extends not only to salvation but to every aspect of worship and obedience. We do not decide what pleases God through majority opinion or tradition. God has spoken, and His Word alone is authoritative (2 Timothy 3.16-17).

The Pharisees believed that their detailed fence laws safeguarded God’s commands, but in reality, these traditions became obstacles that kept people from approaching God as He intended. They overlooked—or never understood—that God requires genuine obedience, not just the outward observance of religious rituals (1 Samuel 15.22; Hosea 6:6).

The Call to Examine Our Own Practices

This is more than just a history lesson for our curiosity. Let us take the core message of the application: Which traditions have we accepted uncritically? What practices do we maintain just because they have always been done that way, rather than because of the commands or approval in Scripture?

We need to regularly reassess our traditions and practices to confirm they reflect the truth—Jesus Himself stated that God’s Word is truth (John 17.17). The religious leaders during Jesus’ era were so immersed in their traditions that they failed to recognize how far they had strayed from God’s revealed will. Today, we encounter the same risk.

Practical Steps for Guarding Against Empty Tradition

We shouldn’t just recognize this danger; we need to take concrete measures to protect against it. This is advice for every Christian who aims to worship God in spirit and truth (John 4.24):

Begin by cultivating the habit of asking, “Where is this written?” When someone claims that a practice is vital to Christian faith or worship, consult the Scriptures to verify if it truly is (Acts 17.11). The Bereans were praised not for blindly accepting teachings but for diligently testing them against God’s Word.

Second, differentiate clearly between issues of faith and issues of opinion. Romans 14 directly addresses this, indicating that certain practices are explicitly commanded or forbidden and must be followed. Other issues are part of Christian liberty, allowing sincere believers to hold different views without opposing God’s will. Confusing these categories can result in legalism or license—both serious mistakes.

Third, understand that sincerity alone does not justify mistakes. The Pharisees sincerely believed their traditions honored God. However, genuine sincerity does not turn disobedience into obedience or human customs into divine laws. As Proverbs 14.12 NASB95 states, “There is a way which seems right to a man, but its end is the way of death.”

The Spiritual Reality Behind Religious Performance

Religious tradition often serves as a substitute for a genuine relationship with God. It is much simpler to follow inherited rituals than to develop a meaningful connection with the living God. While tradition calls for mere conformity, authentic worship requires transformation.

Reflect on how we often find comfort in familiar routines. The Pharisees felt secure in their traditions because these practices were predictable, controllable, and measurable. They could simply check off requirements and think they were righteous, all while neglecting God’s Word in their hearts. Jesus highlighted this superficial religiosity: “This people honors me with their lips, but their heart is far away from me. But in vain do they worship Me, teaching as doctrines the precepts of men” (Matthew 15.8-9 NASB95).

The Origin and Significance of Our Traditions

It’s crucial to honestly consider where our traditions originate and what they truly mean. Are they rooted in Scripture, or have they developed through cultural choices, historical happenstance, or well-meaning but unauthorized changes?

Some traditions are simply matters of convenience or custom—neither mandated nor prohibited by Scripture. We may choose to keep or change them based on wisdom. However, when tradition conflicts with Scripture or supersedes God’s actual commands, we must have the courage to set aside human traditions and follow divine authority.

The religious leaders Jesus challenged had broken God’s clear commandments by following their own traditions. He pointed out their use of “Corban”—a practice where resources were declared dedicated to God to bypass the fifth commandment’s demand to honor parents (Mark 7.10-13). Despite this apparent contradiction to God’s Law, they vigorously defended their tradition. It shows how easily tradition can blind us!

Ensuring Our Customs Serve Rather Than Supplant Truth

We need to stay alert to make sure customs do not mask the true intent of our actions. This awareness calls for more than just occasional checks—it requires ongoing dedication from hearts committed to Scripture’s authority. We must uphold the principle that Scripture alone should be the ultimate authority in faith and practice.

Reflect on these important questions: If all traditions were taken away, would your faith stay strong because it is based on God’s Word? Or would losing familiar practices make you feel lost and uncertain? Are you worshipping God in line with His revealed will, or just following the accepted ideas of past generations?

The Jerusalem church encountered this challenge when tradition risked overshadowing truth. Jewish Christians, ingrained in ancient practices, found it difficult to accept that Gentile converts did not have to follow ceremonial laws to be saved. God intervened to clarify that salvation is by grace, not by obeying traditional rules (Acts 15.1-29; Galatians 2.15-16).

The Freedom Found in Scriptural Authority

Here’s a liberating truth: By grounding our faith and actions in Scripture rather than tradition, we find freedom rather than limitations. God’s Word serves as a lamp to guide us and a light to illuminate our path (Psalm 119.105). His commands are not burdensome but bring life (1 John 5.3). Letting go of unapproved traditions allows us to open our hands and receive what God truly intends to give.

The Japanese will keep celebrating Christmas with KFC, unaware that this fifty-year-old tradition isn’t linked to actual Christmas customs. While this harmless confusion causes no harm, problems arise when religious tradition replaces divine command and human customs overshadow biblical truth. In such cases, the core foundation of faith is compromised.

Walking in Truth Rather Than Tradition

Let’s honestly assess our hearts and actions. Instead of asking “What have we always done?” we should focus on “What has God commanded?” We should seek worship rooted in Scripture rather than sentiment, doctrine grounded in revelation rather than routine, and obedience driven by love for God rather than mere human expectations.

As we transition from this Christmas season into the new year, let us renew our commitment to the primacy of Scripture. May we find the courage to let go of traditions that oppose God’s Word, wisdom to preserve practices that align with His purposes, and discernment to distinguish between them. Ultimately, our accountability is to God, who has spoken plainly through His Word and calls us to obey Him rather than human traditions (Acts 5.29).